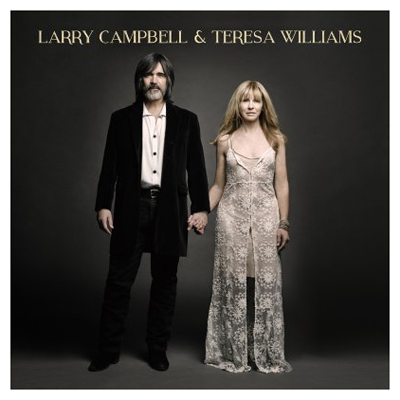

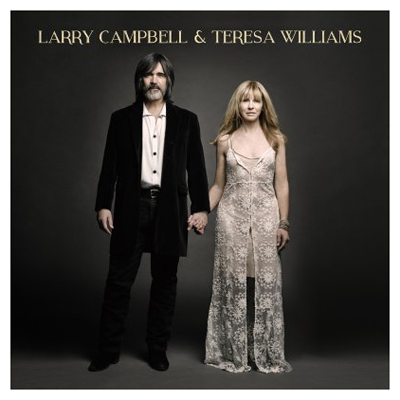

AN ALBUM, AT LAST

By Jamie Malanowski

The act of album-buying may no longer be the mainstream, commercial, megastore-in-Times-Square activity that it used to be but, oddly, for many artists making and releasing an album, it still has the iconic status that it enjoyed in 1964. It’s a landmark, a validation, a State of the Union address, and a new baby, all wrapped up in one. But then there are performers like Larry Campbell and Teresa Williams, for whom an album has never been part of the master plan. The tall, broad-shouldered, easygoing Campbell, now sixty, has been a virtuoso instrumentalist for four decades, backing up one giant after another. His partner, the slender, powerfully piped Williams—self-described as “old enough to have picked cotton before there were machines”—has been a hidden treasure. Both seem surprised that they have become genuine recording artists.

“Everybody has been telling us we should put out an album for years,” Campbell said recently. “And we kept saying, ‘Yeah, yeah.’ I never wanted to put out an album. I just wanted to play guitar in a band.” “Why don’t you have a CD?” Williams said, imitating one of those generic everybodies. “My brother has a CD. My cat has a CD.”

“So finally we said, ‘O.K., fine, let’s do this,” Campbell said. “We’ll walk down this road until we hit a dead end, and then we can get on with our lives. Well, the album hasn’t even been released yet”—June 23rd is the magical date when “Larry Campbell & Teresa Williams” will fulfill the dream neither ever really had—“and, far from a dead end, the thing keeps expanding.” The couple, much beloved in greater New York, has added a Midwestern tour, a national tour in which they will open for Jackson Browne, and an appearance by Campbell with the Roots on the “Tonight Show.” “It’s a curious feeling when you find out your work’s being well received,” Campbell said.

It’s more than either ever expected. Williams, though a native of Peckerwood Point, Tennessee, and musically inclined, never gave any thought to taking her voice to Nashville. “There’s a lot of ‘Who does she think she is, gettin’ above her raisin’?’ where I grew up that discourages that sort of dreaming,” she said. Instead, Williams came to New York to pursue acting, and managed to make a creative living without quite getting her talent and timing and luck permanently aligned. She first connected with Campbell in 1986, when she heard on the radio that the Bottom Line, then one of the top music clubs in New York, was holding a singing contest, and wanted singers to submit demo records.

Williams was determined to cut a demo record and, with recommendations from friends, quickly collected a backup band, which included Campbell, a budding studio musician who could play anything with strings, short of a squash racket. As it happened, she lost the contest but sparked a mutual attraction with Campbell that was not fated to ignite until nearly a year disappeared in rom-comish misunderstandings and missed opportunities. When they at long last connected, Campbell wooed her with a Louvin Brothers CD. “I just knew this was it,” she says.

Theirs was not a conventional marriage. For fifteen years, Campbell and Williams were frequently separated by work, especially during the eight years Campbell spent backing Bob Dylan on the Never Ending Tour. “It was never hard to stay in the relationship,” says Campbell, “but it was hard to give it the attention it deserved. I’d be out with Dylan for a year, and I would get home, she would be touring with a play. It was challenging.”

Soon after Campbell left Dylan, he got a call from Levon Helm, the legendary singer and drummer of The Band, who had begun throwing small house concerts, called Midnight Rambles, in his home in Woodstock. “Come on up and make some music,” Helm told Campbell. The invitation proved to be a turning point in the fortunes of both men. For Helm, the Rambles helped reëstablish a disappearing career; for Campbell, it was time of growth. Stepping out of backup mode, he led the tight, talented Ramble band, often numbering a dozen or so players, and managed to make them all feel happy and appreciated. He also produced or co-produced for Helm three Grammy winning albums, and even allowed himself to occasionally sing lead, releasing unto the world an expressive baritone that had been largely silent.

“When Larry started to play with us, our trumpet player, Steven Bernstein, and I just looked at each other,” says Erik Lawrence, saxophonist for the Midnight Ramble Band. “We knew right away he was a very special kind of musician, with incredible ears and an impeccable sense of composition within the composition. Even at the highest echelon of musicians you don’t find that very often.” After just a few sessions, Helm’s daughter Amy, a singer in the band, encouraged Campbell to bring Williams into the mix. “Teresa brought a whole level of depth to the band, a sweet soul that perfectly harmonized with Amy’s voice,” says Lawrence. For the first time in their marriage, Campbell and Williams had found something that rewarded them professionally and personally in the same way at the same time, and their careers have dovetailed since.

Like the music at the Rambles, the new album is a mix of country, blues, gospel, and rock and roll. “There are eleven songs on the album, and probably one hundred and eleven that we thought about putting on,” says Campbell, who wrote eight of the tracks that were eventually chosen. “At least in my head, there is a cohesion to these songs, with elements of Teresa’s rural upbringing and my New York City upbringing.” Among the highlights: the romantic “If You Loved Me At All,” the amusingly droll “Bad Luck Charm,” the country-poppy “Surrender to Love,” the sad ballad “You’re Running Wild,” (with drums by Helm, in one of his last recordings before his death, in 2012), and the astonishing cover of Rev. Gary Davis’s “Keep Your Lamp Trimmed and Burning.” Williams’s fervent, insistent warning of the coming Judgment Day withholds nothing, and should become part of the official soundtrack for any apocalypse that may be on the way.

“My mother gave me a healthy distrust of fame,” says Williams. “She had her feet on the ground and saw it for what it was. For us, the point was always to express ourselves, not to have a career.”

“Yes, to express the joy of music,” agreed Campbell. “But this is nice. This is nice.”